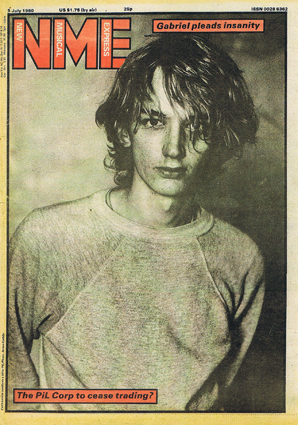

Keith

Levene:

NME, July 5, 1980

Transcribed (and additional info) by Karsten Roekens

© 1980 NME / Chris Bohn

PUBLIC IMAGE LTD. CORPORATION EXECUTIVE REPORT TO SHAREHOLDERS

No Dividends on Live Gigs – Wimpy Bar Undertaking Given – Boardroom Putsch Against Mr Wobble? – PIL Unveil Plans for Film Division. Sir Keith talks bluntly to EEC management consultants Chris Bohn and Anton Corbijn (pix).

No Dividends on Live Gigs – Wimpy Bar Undertaking Given – Boardroom Putsch Against Mr Wobble? – PIL Unveil Plans for Film Division. Sir Keith talks bluntly to EEC management consultants Chris Bohn and Anton Corbijn (pix).

Public Image Ltd. and America hardly seemed made for each other. Yet having successfully defied Britain's star caste systems and ugly myth makers, earlier this year PiL suddenly decided to take on the world's grossest rock and roll machinery at their own game. Who came out on top depends on who's doing the scoring.

Despite their rigid no-tour policy, they compromised themselves a little by agreeing to a nine date schedule spread across a month and the breadth of the US. The manoeuvre was set up to ease the release of 'Second Edition' by Warner Brothers [1] on an American public, whose belated interest in punk/new wave – with whom PIL are no doubt associated – meant taking The Clash to their hearts.

From this side of the Atlantic we got an odd view of this sudden display of business acumen, as seen through the perceptions of bemused American observers. Firstly, there was the spectacle of the concerts themselves: wild and strange affairs that John Lydon and Keith Levene mocked and ridiculed with their refusal to get drawn into the performing routine, while the humane axis of Wobble and Atkins, more concerned for the audience, tried to establish a sense of order. Secondly, there came a spate of solo Lydon interviews, a surprising departure from the corporate press meetings we're used to here. Things didn't appear to be as solid as they once were.

America proved to be a cathartic experience for PiL. It was a test of strength that shook them up considerably, polarising certain aspects of their make-up, destroying forever other ideals and aims.

"What America amounts to is that we don't ever wants to gigs again," reports a fraught Keith Levene, "and we definitely don't want to be a rock and roll band because of it. About two of the gigs were good, and all the others were just hell, you know. And sometimes we ended up by abusing the audience by playing rinky-dink tunes and they didn't know the difference. Other times we just did the set and it was awful. That was America really – all they want is rock and roll stuff."

Closely following their return home came rumours of PIL's accelerating demise. Martin Atkins, drummer of nine months standing, announced his departure. He intimated, too, that Wobble was no longer happy with the corporation.

"When it comes to members of PIL," says Levene, "Martin Atkins is no longer with us. But he was never part of PIL, he was just like a hired drummer, and as we won't be playing live ever again, we no longer need one. As for the rest of PIL, it consists of me, John, Jeannette Lee, Dave Crowe and Wobble ... um, at the moment. It's just, like ... as a thing PIL is internally changing. We hope to the advantage of the public and us ..."

Just before the story broke of Atkins' split, Levene had invited 'NME' to talk – at a guess about the corporation's shaky state. He wanted to talk alone. This in itself was novel, as he'd always appeared to be the least talkative at their corporate gatherings.

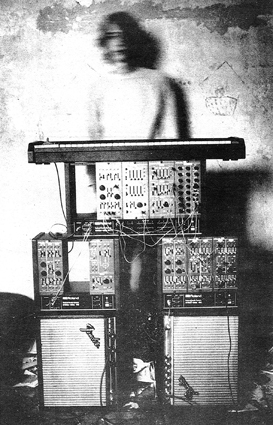

As I waited last week in Virgin's press office, a press officer dealt deftly with the sudden influx of calls from news editors with a scent of Atkins' departure. Levene arrived late and extremely agitated, looking deathly white. He apologised, saying he'd been up all night toying with a new synthesizer system. We adjourned to a quieter room and made three unsuccessful attempts to start a conversation, the last one going 40 minutes before Levene decided he was too inarticulate carry on. More agitated than ever, he called PIL film-maker Jeannette Lee to remind himself why he wanted to talk in the first place.

"Yes, hmmm, huh-huh, yes. Yes, I've told him that. Not yet ..."

More relaxed, he replaced the receiver and after a brisk walk to a new office we started again, this time successfully. Contrary to Levene's legendary 'difficult' behaviour, he opened up on almost everything, though he spoke evasively about PIL's ongoing 'internal changes'. As intimated earlier, letters from abroad indicated that PIL were not as united as they had once been – for instance, the Lydon solo interviews and now Levene's request to speak alone.

"I'm glad you brought that up," says Levene, finally calming down. "It wasn't like that. A few weeks before we did the US tour, John and me went over to do some promotion and did some 20 to 25 interviews together. [2] And I spoke at length for hours, but when the press came out it was all John Lydon, right? And that hurt my feelings. I don't care about the star aspect, it just bugged me – I told them loads of things and they never wrote them down. It was like John knows everything. He doesn't like it either. There's nothing wrong between me and John – we're really together. The reason I asked to do this interview alone was because I'd never done one alone, and I just thought I'd like to, you know, talk about music, talk about me a bit more. The thing is with what PIL are doing now, apart from Dave and Jeannette's thing, what John wants to do and what I want to do are similar, so talking about me is like talking about me and John. I just wanted to put the points over because John won't talk at length. He just gets into 'You either like it or you don't buy it!' whereas I'd be more into answering questions at length."

Evidently Wobble, by lack of reference to him and through biting criticisms, isn't in favour with Levene at of moment. His position is rendered cloudier by Lydon and Levene's imminent departure to the States without him to work on a movie soundtrack for Michael 'Woodstock' Wadleigh, [3] while Wobble apparently will stay in Europe pursuing solo projects. [4] The release of his album 'The Legend Lives On – Jah Wobble In Betrayal' also incurred the guitarist's wrath, principally for its alleged use of rhythms that had been discarded by PIL and that Levene wanted to stay that way. [5] In his view PIL means total commitment, and anything released would appear under the corporate heading with the full knowledge of the others.

"We can all do solo work, yeah, but it comes under PIL, not Jah Wobble. We always knew that Wobble was making the record, but we didn't know anything about it, so I don't see that it connects with PIL at all – whereas I see any the stuff I do as always connecting with PIL. The thing that Wobble did was a mercenary act. I didn't like him using backing tracks from PIL that I didn't want people to hear. I don't personally like his record at all, but Wobble thinks it's a masterpiece which, if the people don't pick up on it now, they will later – he even compared it to Van Gogh somehow!"

A current persona non grata he may be, but I felt that Wobble's album was a quietly understated, likeable affair with a few outstanding tracks, like the earlier single 'Dan MacArthur' – which even Levene concedes is good. It's difficult to imagine it's good nature causing so much offence. There must be something deeper at the root of Wobble and Levene being at loggerheads.

The guitarist points to Wobble's behaviour in America. Apparently he was getting sucked into the rock and roll routine of giving the kids an encore, because they'd paid their money. Yet at the same time, according to Levene, he would say he was fed up with playing 'Public Image' to "get the kids going".

"I said to him 'Were you doing that? That didn't occur to me ever!'" asserts Levene. "I never thought we'd do this to get them going, this to get them satisfied and this to get them off. Never. It was always a totally open situation. Apparently at the L.A. gigs I was walking around without my guitar on and I did not notice for six or seven minutes. I was just shouting and talking to the audience, yeah? At other times I did other odd things, like sometimes I'd fling food at them – it was always a totally open situation."

With all this talk alluding to Wobble's misdemeanours, and at other points to his exclusions, I wonder whether PIL would exist without any one of its present component parts.

"Hang on, let me think about this. It's a funny question ..." He hesitates. "The way I see it, quite honestly, is that if Dave, Jeannette, me or John ... or anyone ... left, it wouldn't be PIL. I just see us as one ... I don't know. Ask me that question again and I'll give you an answer."

Okay, do you think that PIL would split if any one of it's present members left?

"Yes, I do," he answers categorically. "If any one of us left then PIL would no longer to exist. Yeah."

If that is the case, I hope any rifts are quickly healed. Levene's commitment is undoubtedly total, so what does he demand of fellow members?

"Honestly – total honesty. And I get it from everyone apart from Wobble."

Oh no ...! Let's change the subject. PIL were formed in 1978 by Levene and Lydon, two survivors from unsavoury punk experiences, with Jah Wobble, the then non-musician, defining their sound with his highly inventive, sonorous basslines. Created as a healthy antidote to rock and roll excess, the three, with early drummer Jim Walker, established themselves as an independent corporation. Making records was supposed be just one of their functions. Levene was an early member of The Clash. The excitement of his first punk band was only temporary.

Oh no ...! Let's change the subject. PIL were formed in 1978 by Levene and Lydon, two survivors from unsavoury punk experiences, with Jah Wobble, the then non-musician, defining their sound with his highly inventive, sonorous basslines. Created as a healthy antidote to rock and roll excess, the three, with early drummer Jim Walker, established themselves as an independent corporation. Making records was supposed be just one of their functions. Levene was an early member of The Clash. The excitement of his first punk band was only temporary.

"All I knew at the time was that I really wanted to be in a band. [6] We really fired at the time, me and Mick Jones." (Strummer hadn't arrived yet) "We had a good thing, but Mick was always Rock and Roll Mick. I didn't realise then just how much I resented rock and roll. In the end it was either me or Mick. Any numbers I got together they didn't really understand, so I eventually I left and they really wanted me to go. But The Clash isn't really my roots. It's, like, the same thing that happened to Eno and Roxy Music, happened to me and The Clash – they just weren't me, as you can see from where they've gone. Compare PIL and The Clash now and you can see the difference, right?"

His distrust of rock and roll isn't directed at the originals, but those who continue to repeat them today. Citing his early tastes as The Rolling Stones, he followed rock's developments through to the'fill your head with rock' period of The Nice and Cream, believing in its importance right up until Mark Bolan turned commercial in the early '70s.

"That's when bands all became the same and it got very boring. Funny thing was that I never realised at first that rock – The Rolling Stones – all came from black music, the blues. And I really came to hate all those '50s Chuck Berry riffs. I love it for what it was, but all the rock and rollers I know, like ex-Rich Kid Glen Matlock and all that lot, makes me ill. They are all so into that and think that it's so important – if only they'd fucking get away from it, into something that is important ... My personal thing has never come from black music, and I'd hate to be involved with the blues or anything. I never get the blues. I might get down, but the blues haven't got anything to do with me, right? When I left The Clash I joined a band called The Quickspurts, [7] and I told them that if I could amputate their little fingers I would stay with them, because I hate all that 12-bar shit, you know?"

PIL consciously and deliberately avoided the usual rock and roll paths. It meant, says Levene, de-learning rock guitar, which he hated as such anyway. Wobble's presence was integral to the process – not being able to play, he would invent his own bass lines for Levene to work from, and additionally he wouldn't know whether Levene was playing the 'right' thing anyway.

The results on the 'First Issue' album were marked, but at the point the band still seemed to be relying heavily on each other, which meant that riffs were often sustained too long and without enough of variation.

'Metal Box' though was justification of the PIL approach. By this time Levene, Wobble and Lydon had grown sufficiently confident of their own abilities to stray away from each other. Levene would come in at glancing tangents to Wobble's bobbing bass, shunning heavy chording and extensive soloing for a more exhilarating, rapier thin sound that would whip its way around the murk quite brilliantly. The effects are still liberating in their freshness, despite the plethora of guitarists who have since adopted Levene's guitar-as-sound method. Commenting on their progression, Levene says:

"'Metal Box' was an example of me getting into sound more and John getting into the mixing desk more, which meant therefore more experimentation in the studio, using it like a mechanical synthesizer almost. On the first album we had the numbers and recorded them with as much bass and treble as possible, and with as little rock and roll as we could get away with. With 'Metal Box' we had the numbers, but this time we got into producing them as well."

As D.A.F have correctly pointed out, instrumentation has as much to do with present music patterns as the technicians who use them. PIL have fortunately thus far avoided falling back onto them. As to their future, Levene has almost dispensed with guitar altogether, forsaking it for synthesizers. Though the PIL synth room has apparently always been the showcase of PIL's South London base, [8] they're now following through more seriously the experiments began on 'Metal Box', to which Lydon contributed to the orchestral parts of 'Swan Lake'.

"It was great to watch him do it, because he did them totally out of tune to the rest of the track. Yet they were just fucking great and so important to it," Levene smiles.

But haven't the pitfalls of electronic pop been made only too apparent by the limitations already run into by the currently successful exponents of the style?

"I don't know the limitations that you're talking about. It's like the rock and roll guitar thing that I've broken away from. It's like all those fucking people and Eno, and I hope I don't end up sounding like either of them. But it's very hard if you've got a string synthesizer or Moog, not to end up sounding a bit like Eno. He didn't establish patterns, but he definitely broached new barriers very early on. No one yet has done anything else different from him – as far as I can see."

Much to Lydon's chagrin, Eno is increasingly influential on Levene's outlook, not only for what he's done in rock, but also for a shared interest in functional and mood musics. Surprisingly to some, including me, Levene considers 'Metal Box' to be mood music, whereas I'd consider even those tracks that sound superficially easy, like 'Chant' and 'No Birds Do Sing', too turbulent to take passive role when it's playing. Levene thinks otherwise.

"I think that's where people get PIL wrong, because the thing is, I know, when you initially hear it, it just sounds like very fucking heavy and intense, yeah. But if you sort of introduce yourself to it then you realise it's the ultimate mood music."

Eh? Please explain ...

"People don't realise there's 32 levels of different things you can get off in PIL music – like, if you listen to 'Death Disco' three times you think it's a good disco track, but if you listen to it thirteen times, you think fucking hell – there's a whole spectrum of stuff that you can draw from it. PIL's music doesn't meet the eye or ear on first appearance or listening."

Director Michael Wadleigh recognised it's various levels, claims Levene. 'Metal Box' was presented to him along with others from the Warner's catalogue as possible contenders for a soundtrack to his upcoming, as yet unnamed, movie [9] about the relationships and similarities between wolves and Red Indians – their outsider sensibilities, pack hunting, instinctive behaviour. Picking up on 'Metal Box', he contacted PIL.

"I met loads of guys in America who spoke about PIL, but he was the only one who knew what he was talking about," says Levene. "It was very interesting what he was saying. He had a lot of respect for us, and he's the only one who could pick up on those 32 levels of moods I was talking about earlier. He could pinpoint and talk about them on certain tracks – and I knew what he was talking about, because I made it. He offered us a third of the soundtrack and I hope that we impress him enough that we can do all of it. He wants us in our music to possibly find sounds for what a wolf sees and hears and smells when it sees a human, and so on. We might just end up doing vocal sounds through John and treating them."

How does John feel about PIL as mood-makers?

"John's really into it being dance music, but the good thing is that it's not obviously mood music. It's, like, down to the listener – it doesn't have to be mood music if you're not in the mood for it."

But what is it about muzak that fascinates him?

"I've always been into Wimpy Bar music, Golden Egg music, you know? You got all these musicians who're probably technically brilliant, creating an amazing juxtaposition of feeling. It's just incredible, you don't know where it comes from, you know? I was going to make an album of music called 'Music for Wimpy Bars'. There's a certain thing about it, I don't know what, but I'd definitely expect to hear that sort of thing in a space capsule. The whole idea, the whole thing of doing mood music, is so important, because it's there and so hard to avoid. I'm not just into rock, I've got all these moods and feelings and they've just got to be out. That's why I'm definitely into doing film soundtracks ..."

Now no longer a band of such, more a corporation, the added emphasis on sound and vision is designed to bring PIL's other members into the creative process. Dave Crowe (their part time accounts man, photographer etc.) will be helping Levene construct a multi-purpose studio for recording, filming and video, the ultimate dream being for PIL to put out video albums made by themselves and Jeannette. Sounds like a bit of a dream, maybe?

"It's not even an idyllic set-up, it's realistic. It doesn't just mean pictures of the group playing music, it's just bullshit doing that. But we're redirecting our concentration onto sound and vision, vision especially, because going around as a pop band playing live seems to be communication to the wrong people."

Sometimes talking to Levene, and Wobble too for that matter, sounds like a conversation with a publicity blurb for a particularly zippy firm, the way all those saleable catchphrases roll off the tongue. Obviously with the seeds of the corporation concept planted, those cute little slogans sprout easily, as do convenient hooks vaguely queasy, callous explanations for individuals' sudden departure, particularly their long string of drummers.

And if the PIL corporation sometimes sounds like a retreat from reality, they'd probably argue that it was a strategic one, allowing them time to gather forces and ideas for their collective assault on Virgin and their future outlets. Levene believes that their markedly different approach will no longer work against them with their parent company, although he'd earlier complained of them cutting PIL's next recording advance by half. So the corporation is now looking for additional ways of financing itself outside the record industry.

"I'm thinking about getting money from companies like ITT, if it's possible," states Levene. "I'd rather be financed by them than a record company, because I don't necessarily want my money to make an album, but as facility for a form of creative output."

What about ITT's dubious involvement with the CIA and other shady activities?

"We can't do anything about them, so I just like the idea of getting money from them. Perhaps draining them of some money they might spend on arms, or whatever. It's a bit cynical. But it's important to check things out, I mean, Warner Brothers ain't my ultimate company. I'm not interested in politics, I don't like talking about politics at all. Maybe I don't understand enough to talk about them. There's party politics and people politics. The first doesn't interest me, they're just different amounts of bullshit to me. People politics are important though, but people are not together enough."

Hence the formation of organisations.

"Hence the formation of PIL!" he ripostes. "Our politics were not to have middle-men, in the form of managers, producers, artistic directors, secretaries, whatever. Hence we run our own affairs. Like, PIL were always a limited company, and the idea was for it to be more a corporate thing than a band thing."

How does he take to business dealings?

"It scares me sometimes that we might lose PIL, or be put inside for tax. I worry about it, maybe because my old man's Jewish. My mum isn't, nor am I, but maybe I inherited worrying from my dad. John doesn't worry about it at all, he just lives through it. But I want to do the business side of things, so I worry – I'll learn to get over it."

Lack of management caused PIL a few problems in the States, where they found themselves confronting the record biz bureaucracy of myriad small departments like artistic direction and artist development, all with preconceived ideas of how rock and roll should be run.

Lack of management caused PIL a few problems in the States, where they found themselves confronting the record biz bureaucracy of myriad small departments like artistic direction and artist development, all with preconceived ideas of how rock and roll should be run.

"It's just terrible," moans Levene. "You're trying to tell them your ideas and all they say is 'You gotta get a manager!' We say we want to talk directly to the record company, and they're still going on – 'He doesn't have to be called a manager.' It's really flogging a dead horse. We got this guy [10] from artist development on the road, right, supposedly watching us develop. And the only development that I got from the tour was not to tour or have anything to do with rock and roll anymore. That's how much I developed!"

Rock and roll alters people's perceptions. It's a two-way thing. Groups are given great expectations by record companies and are eventually let down badly. And the public, hankering after stars, treat musicians as such, and soon neither side knows how to act.

"It's a real drag though," says Levene. "But I can understand new bands coming up and wanting to be stars. I understand their motivations and values, but if they realised it was mostly illusion they wouldn't get deluded – and probably wouldn't have formed the band in the first place. PIL was the nearest thing I wanted to get to being in a band, and now we're not touring it's everything I always wanted it to be. I really think the band as such is the old-fashioned part of it. You know, people should learn from history that it's not like that anymore."

Late on in our conversation Levene had completely recovered from the nervous extra-helpfulness which led to the inarticulate beginning. Even when we were having problems communicating, it wasn't so much from his reputedly difficult, as in moody, nature, as his desire to express fully what he was saying. Stories of his surliness, especially with one-time drummer Richard Dudanski, cloud his reputation. Like the time soon after Dudanski joined, when PIL played a surprise gig at Manchester's Factory Club, [11] which accelerated Dudanski's disappearance.

"I'd said let's do the gig, right?" replies Levene. "And then I realised that Dudanski hardly knew any of the numbers and we had a row which didn't have anything to do with anything apart from speed paranoia on Dudanski's part, but it wasn't that I wanted the gig and the rest didn't. Like, I'm friends with Dudanski now. I am difficult to work with, but those I do work with understand me. So's John – we're all fucking difficult to work with. We're temperamental, but because we know each other it's not a barrier. They'll just laugh at me being difficult, and John calls me a yapping dog sometimes. I'm known as Bad Baby, and John, I call him Big Baby. That's because in the studio, if things aren't right, I'm telling him that something's no good, you know?"

How about PIL's attitude to their public? The feedback they've received is mixed. Some people consider them Johnny Rotten's new backing group, others as a joke. Many are still be intimidated by them, both as individuals and because of their unconventional approach. Then there's the live 'Stranger In A Strange Land' theory that audiences are easily manipulated.

"It surprises me that people would rather be scared of us than find us great for getting into new things, making original music," says Levene. "They just don't seem to pick up on that. It's like anything new, angry and truthful and realistic gets avoided. Capital Radio would avoid us. It's just like special programming to keep the fucking morons quiet, but we're not morons and I don't think people are morons ... though I'm changing my opinion."

Why?

"The general lack of feedback that PIL have had. Just the way people are in general." He later modifies this. "I'm observing people all the time. I won't say I like them, but with every individual I'm totally open, until I kind of realise where they're at, and then I decide whether to give myself to them or not. I don't mind being hurt by people, but I won't let an arsehole hurt me like I used to. It used to really fuck me up. I don't feel a bighead about it, but I'm more open to people than anyone in PIL. I'd be the last person to say 'Oh that fucking moron!', you know?"

Artists are by nature selfish and they'll go to extraordinary lengths to protect their personal vision from outside interference. An artist will only work in a group or organisation as long as his form of expression isn't compromised, and if he can't get his own way, he'll act ruthlessly to obtain it.

Even so, when Levene cynically refers to Martin Atkins as a "former employee" of the PIL organisation and talks hatefully of present member Jah Wobble, we outsiders can only look on uneasily at his seemingly callous behaviour, and perhaps worry how such talk will affect PIL's future, despite Levene's assurances of their stability.

Yet without that essential selfishness, PIL wouldn't have come anywhere near this far. Their music depends on the brave juxtaposition of their individual extremes, only working because each member is fully realising his own ideas without hindering the others. But it would be disastrous if they refuse to accommodate each other under the collective PIL umbrella.

PIL so far have been a vital independent force in modern music. The corporation re-shapen to take in movie and video-making will place even greater strain on their emotional and material resources. I hope they've the strength to support their additional ventures, as many of us have invested too much for them to give up on us now.

![]()

(from the 'T-Zers' section of the same issue:)

"New cometh from Germany that Jah Wobbleski and Holger Czukay (pronounced Zcewlarken), the Can man, are working on a joint project. In a radio interview compered by Angus MacKinnon the pair played some happy marching tunes which our informer reckoned sounded "pretty damned hard, I don't mind telling you." The debonair Wobble is now exulting in monies derived from the PIL coffers [12] but is adamant that all is well bandwise ... Actually Lydon and Levene are busy as bees writing a film score about wolves and Indians for one Michael Wadleigh (producer of 'Woodstock') ...

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Warner Brothers actually released just the cassette version of 'Second Edition', as the vinyl version was licensed to Island Records.

[2] Lydon and Levene even staged a press conference at 'The City' discotheque in San Francisco (3 March 1980).

[3] Lydon and Levene flew to New York in late June 1980 and infamously appeared on American TV ('Tomorrow' show, NBC, 27 June 1980).

[4] By mid-June 1980 Wobble was in Germany and worked with Holger Czukay on their 'How Much Are They?' EP (released 22 June 1981).

[5] The album included an instrumental dub of 'Another' (titled 'Not Another') and the original Wobble version of 'The Suit' (titled 'Blueberry Hill').

[6] In 1975 Levene tried to talk Ultravox drummer Warren Cann into getting him into Ultravox: "He kept pestering me to join the band - "C'mon! I'm a much better guitarist than your guy!" I'd say, "Listen, Keith… all you ever listen to is all that fucking widdly-widdly jazz rock Frank Zappa/Todd Rundgren Utopia crap… Forget It!" (Warren Cann interview Electrogarden.com, 2002)

[7] The Quickspurts were Steve Dior and Barry Jones (who later formed London Cowboys). They rehearsed in late autumn 1976 and broke up before they ever played a gig.

[8] PIL used Rollerball Rehearsal Studios in Tooley Street, London SE1.

[9] 'Wolfen' (premiered in the US on 24 July 1981). PIL didn't get the soundtrack.

[10] Larry White, who in spring 1983 became PIL's manager.

[11] 18 June 1979.

[12] According to his autobiography, Wobble helped himself with the band's coffer after returning from the US tour.

![]()

© Anton Corbijn