PiL Interview:

Melody Maker, May 24th, 1986

Transcribed (and additional info) by Karsten Roekens

© 1986 Melody Maker

APOCALYPSE NOW

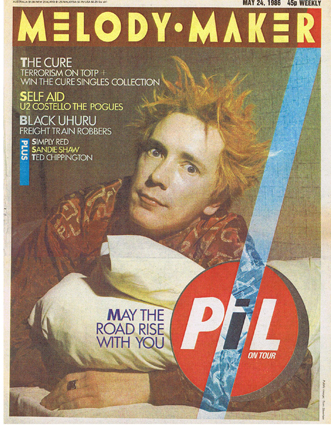

Contrary to hardened public opinion, JOHN LYDON reckons No Future's a thing of the past. Touring with a new PIL, he preaches to CAROL CLERK on the nuclear threat and what the hell to do about it. Oh, and he drinks a lot as well. Peaceful pics: TOM SHEEHAN.

Contrary to hardened public opinion, JOHN LYDON reckons No Future's a thing of the past. Touring with a new PIL, he preaches to CAROL CLERK on the nuclear threat and what the hell to do about it. Oh, and he drinks a lot as well. Peaceful pics: TOM SHEEHAN.

Somebody told me John Lydon liked a drink. And this was indeed a large crumb of comfort. Suddenly it was possible to establish some common interest. Suddenly there was a sense of relief that business could be taken care of in the mutual territory and relatively congenial environment of the hotel bar. There was additionally something attractive about a little Dutch courage.

Lydon, of course, is the man whose reputation looms large before him like a death threat. He is one of two cartoon characters invented and embraced by the media. He's the wild-eyed, acid-tongued tormentor who eats journalists for breakfast and throws them up in lumps before lunch. Or he's the awkward, godlike genius who must be approached not only with caution but with an earnest and obsequious reverence. He would not, naturally, show any signs of belonging to the human race. The man would be either a complete monster or a complete misery.

We were passing the afternoon at the Edinburgh Dragonara Hotel in something called the Granary Bar when Lydon breezed in, all fiery orange hair and a smock that trailed down towards knee level. I noticed his dimples and laughter lines around blue eyes. He sat down, joked, smoked Silk Cut and did not deliver The Stare. The conversation circled around the tour, the events of the tour and the most unlikely would-be groupies of the tour, the pair of 12-year-olds who only a couple of nights before had subjected the great man to an act of genuinely indecent assault.

"I was shocked," he reflected. "Shocked."

And so began the collapse of preconceptions, the reminders to those of us who should have known better that cartoons do not exist in real life unless you want them to.

Lydon, it seems, is predictable only for his unpredictability. A preliminary inquiry about Sigue Sigue Sputnik revealed that, far from wanting to claim any credit for co-creating the Pistolian tactics now employed by Tony James' boys, far from cheering them on in their quest for the ultimate publicity stunt, he's quick to be dismissive: "I'm not sure what Sigue Sigue Sputnik is apart from an eloborate joke, and I think the joke is on themselves. They're not an ongoing force."

At the same time he can be generous towards some of life's more natural easy targets, like George O'Dowd: "I thought he was alright. He came up and said hello and I said hello back, but he didn't need to do that. Most people in this business are so precious about themselves. Good luck to him, you know. I could see the possibilities of him being able to sing, much more so than me. I howl affectionately."

John Lydon is in business in 1986 because, and in spite of, his past. As a result the things he gets pulled up for are also the things he gets away with.

He can stay out of the papers, out of the charts, out of our minds long enough to commit commercial suicide. He neither wants nor attempts to survive on any terms other than his own. He simply comes back and people want to know all over again. The extreme fans are waiting because he is who he is and was, and therefore everything he does must be brilliant. The normal rational fans are waiting because they're interested. The extreme non-fans are waiting too. They want to argue about him in pubs, want to call him a parody of himself because he hasn't changed dramatically enough to be called a chameleon or a conman, and damned if they're gonna look for any consistency or identity in here, damned if they're gonna find anything friendly to say. This is John Lydon, after all.

And he wins in the end. The records are in the charts, the band is on 'Top Of The Pops', the punters are at the gigs, and Lydon has the satisfaction of knowing that he's purely been pleasing himself and it's worked. Again. His detractors, as he's fond of saying, can "eat shit and die."

In the midst of the divided opinion that surrounds him, Lydon is hardly impressed with the notion of himself as something controversial. Any inquiries in this direction will be met with a flippant "I think Cliff Richard is controversial. Anyone who's lived with his mum for that long is definitely suspicious."

He is however interested in the idea that by making his own rules and calling the shots he can continue to be "a serious threat, chipping away at the foundations" of the music industry or any other bureaucratic establishment that he happens to collide with.

And if he is a persistent thorn in the flesh, then he's probably been causing Virgin Records some considerable discomfort. There was, for instance, a head-on confrontation concerning Lydon's determination to release 'This Is Not A Love Song'. More recently there appears to have been a conflict over Virgin's willingness to promote PIL records and now the PIL tour.

"It's one of the tragedies that the record company seem to inflict on me from time to time," he complains, settling down to a post-gig [1] gallon in the Dragonara cocktail bar. "They're not exactly giving us a lot of money for this tour. They're not helping in any shape of form. I stay with them because I'd be sued to fuck if I didn't. That's the tragedy. I will go on and I will progress, and it's mostly my money that's invested in this tour. I'm doing this for the love, not the money. I love doing it. That's the reason."

Perhaps a small minority of people in the audiences so far had misunderstood their own reasons for being at a Public Image gig. Some had misguidedly imagined that the clocks had not moved forward a second since 1976. Faced with someone who used to be called Johnny Rotten, inspired by their puerile misinterpretations of a character they were probably too young to have known much about in the first place, they had seized their opportunities to register some abuse. Lydon was hit by a bottle at Stoke. [2] At Sheffield [3] someone threw a billiard ball onstage. It didn't get anybody, but the band nevertheless refused to come back for another encore.

"It's the same as it is for Ozzy Osbourne," muses Lydon, a frown of irritation crossing his brow. "There are two or three demonologists in his audiences - does that make him a professional satanist?"

John McGeoch, newly recruited to PIL on guitar, is equally annoyed: "We were sort of expecting a bit of gobbing from some morons who think it's fun, but we also expect people to stop when we ask them to," he explains. "It can be very scary when you're confronted with a lot of people, most of whom you can't see. John was quite brave to get up and confront the guy who threw the bottle. As for the guy with the billiard ball, what a coward! And it was so premeditated: leave it to the end of the show, get your money's worth, and then knock out the singer."

This is not a punk song, and this is not 1976. In the ten years since all of that Lydon has grown up, wised up, seen the world, broadened his outlook and said a firm farewell to the past.

"If only anarchy was not a mind game for the middle classes," he sighs. "It always has been. That's the trouble."

John Lydon stayed away for a while because he was bored, didn't feel like working and therefore didn't. He felt like travelling. And, contrary to popular opinion, he did not disappear into hibernation in some cosy American hideaway.

"I didn't spend the whole time there," he declares. "I go backwards and forwards all the time, I live all over. I've dotted myself around the world. And here's the thing: people are people, no matter where you go. Once you get past the prejudice about accents, then the way's clear. There's good and bad everywhere. Except Iran, it's all bad. Ouch!"

Lydon has a firm authoritative way of talking, rather like a loquacious headmaster. Especially when he's telling you about America.

"I like America because it's absolutely completely mad. It's a brand-new country. It's not established, it hasn't found its feet yet, and it has no culture. That I find entertaining. Let's face it, European culture has had its day. The thing about America is that it's flexible and very changeable. They don't believe in anything more than 25 years old - knock it down and start again! There's none of that here. This stupid feudal system that we suffer from in Europe is our downfall. We should've learned our lesson after the last World War."

Lydon maintains that he can see certain elements of hope in America. And it may surprise certain people to hear that hope is a theme he returns to regularly throughout out discussions. The man who once bellowed the frustration and hopelessness of the world around him, who made 'No Future' the label of the times, is now thinking more in terms of 'No Past', is looking to the future, is worrying about its chances.

"I don't believe in futility ... fertility ... sowing the seeds of discontent," he insists at one point, and the England he's talking about, having lived in it and away from it, is groaning with plenty of discontent of its own. He views the British as a nation too self-centred, backward-looking, narrow-minded and downright lethargic for its own and everybody else's good.

"The trouble with Britain is, it's very insular, it's very involved with itself, it doesn't relate to the rest of the world, and it still has a superiority complex," he storms, steering the conversation irrevocably away from the ordinary stock chat of the official interview and launching into a rant of quite admirable vigour.

"I'd like the British to be a little more open-minded. That's the problem of an island. Nobody's happy here, they're all suffering. Some of those middle-Northern towns, Manchester, Liverpool, are so depressed. There's no hope. In Italy, say, the governments have no say in how the Italians see themselves as human beings. They don't feel downtrodden, they're always on the up and up. Stop blaming other people for not having a job! Bleeding well go out and make one for yourself! There's no law against joining every political party in Great Britain at the same time, go to their meetings! I only speak from experience, follow suit, boys and girls! There doesn't seem to be any such thing as freedom of thought, and that annoys me, and the more left-wing the 'NME' get, the more right-wing I'll get, just to annoy them. It's stupid, a bunch of bastards preaching politics to the people. Surely Oxford must teach something better than dismalness. It's tragic, isn't it, that Oxford graduates can end up on something like 'Absolute Onions'. Poor old Julian!" [4]

English politics is something that infuriates Lydon immensely. Hardly pausing for breath he whizzes straight into a stinging tirade on the Labour Party and, in particular, its left wing.

"They're a riot act, a mob of mobsters, champagne socialists. Class war? They're worse than the National Front! They don't offer an alternative. I've been yelling and screaming about this for ten years and nobody pays any attention to it. Look forward to something! Stop these silly jealousies against the rich, that's all they are. The rich are not a threat, they're just as fucked up as the rest of you. Unite and fight, stop the separatism. Divided we fall. The only thing that's wrong with the Tory party is the people that are in it. That's all you need to do: take that attitude and the Tory party isn't a threat. It isn't a real enemy. You can change these things! All you need to do is fucking make the effort, which is something I don't see too much of in England. This country suffers from apathy. Energy! That's the thing that's missing from this bleeding country!"

This ties in with the lyric of 'Rise', which proclaims that "anger is an energy." Lydon's own anger becomes even more energetic when he returns to the subject of the "bunch of hoo-hahs who are having a go at each other and running our country. It's disgraceful," he huffs. "I really do feel angry about that. They all go home on the train and they all know each other and live next door. It makes me fucking sick. Hypocritical toe-rags! What becomes clear to me is that I'm needed here. Good God, you need me! I'm your conscience! It's not my job to make Britain better. I wouldn't mind helping out, but I'm telling you, it's bleeding hard to get even your own audience interested."

Lydon is not at all convinced that Red Wedge will manage to get any audience interested to the point of any positive or useful action.

"It's too non-specific, it doesn't mean anything to support a lost cause. If they wanna change things, they should be involved directly. They're doing lots of talking about it, to hell with it. It's obvious: them and the others, they won't tolerate individuality. So fuck 'em all. Eat shit and die, like the dogs they are."

John Lydon: "The Ayatollah Khomeini, he does a great gig, it gets the crowd going. He's just a heavy metal band."

Heavy metal appears, somewhat incongruously, to have crept into the conversation quite frequently, and it crops up again when we arrive at the subject of the current PIL album 'Album', a record that took me by surprise on first and subsequent hearings. There's a versatility that I hadn't expected, a big variety of musical pleasures that range from the uptempo rock 'n' roll feel of 'F.F.F.' (Lydon's answer to 'White Wedding'?) through the more familiar huge rhythm sound of PIL on tracks like 'Bags' to the, dare I say it, charming oriental nuances of the closing 'Ease'. Guitars are much in evidence, in 'Ease' you won't have to look far for a solo, in 'Bags' the chords are present and correct.

Heavy metal appears, somewhat incongruously, to have crept into the conversation quite frequently, and it crops up again when we arrive at the subject of the current PIL album 'Album', a record that took me by surprise on first and subsequent hearings. There's a versatility that I hadn't expected, a big variety of musical pleasures that range from the uptempo rock 'n' roll feel of 'F.F.F.' (Lydon's answer to 'White Wedding'?) through the more familiar huge rhythm sound of PIL on tracks like 'Bags' to the, dare I say it, charming oriental nuances of the closing 'Ease'. Guitars are much in evidence, in 'Ease' you won't have to look far for a solo, in 'Bags' the chords are present and correct.

"I got bored with all the attitudes of the past," remarks Lydon. "America does have an influence on this album. I went to some heavy metal gigs and I liked the vibes. The audience went home having a vibe about the gig, and that's missing in England in everything. That's all I wanted to deliver. I never thought this album would be commercial in any shape or form, I thought it would be the absolute kiss of death for me. I grabbed rock 'n' roll by the testicles. I wasn't interested in anything other than I wanted to be uptempo with a serious content."

The content is certainly serious enough. The comforting sound of song titles like 'Fishing', 'Home' and 'Ease' is not reflected in the overall lyrical tone of the album. It warns of impending world disaster, throws uncomfortable images in front of our face and sometimes heightens their impact through the use of contrasting musical mood-making. The rhythmic hypnotism of 'Round' for instance scarcely prepares you for the emergence of "mushroom clouds on the horizon" and the spectre of children dying.

"The nuclear holocaust is imminent," snorts Lydon. "More power to my elbow."

Since the album was written, several terrifying incidents have occurred to bear out is general atmosphere of foreboding, not least Libya and Chernobyl.

"I'd rather be prophetic than pathetic," says Lydon flippantly, but the dimples disappear almost immediately. "Well, what a tragic compliment. I'd rather be proved wrong and be laughed at, but it doesn't seem to be the case. These bastards are going to kill us all off, and of course I bloody worry about it!"

The possibility of playing with PIL was not something that had occurred to John McGeoch. He'd been in regular touch with the band's manager Keith Bourton through his session work for Propaganda and Heaven 17. But he wasn't expecting the phone call.

"I was talking to Keith and I said to him 'What's happening?' and he says 'Would you like to try playing guitar for PIL?' I said 'What, are you serious?' John had just come over from America. We had met before and spent some time together in New York in 1982. [5] We reintroduced ourselves and we got on well, so he popped the question and there wasn't much of a decision to be made, I said 'Oh definitely, let's do it!' I'd just heard the album about a week before that, and I liked it. I was a bit surprised at some of the guitar playing on it, heavy metal guitar solos, which I can't play, but it was quite interesting, the big drum sound and all that. I think we're working more together as a band than PIL ever had in the past. All five of us are quite involved in what's going on onstage, as opposed to John plus backing band. There seems to be more room too, even with the old songs. We are almost loose onstage, and I think it's going to show when we start writing the new PIL album at the end of the tour."

The empathy between the musicians is something that's apparent onstage, something they all refer to often and something that looks likely to keep the line-up together beyond the durations of the tour.

"I'm really excited about it," enthuses Lu, second guitarist and keyboardist. "I hope it will stay together because it all seems really easy. It's a good group, you can really build up moods. It's not technically great, me and McGeoch are hopeless when it comes to playing fast, but we're very very quick on the uptake."

Newcastle, the band agreed, had been the best gig of the tour so far, one of those nights when everything went perfectly and more. [3]

Edinburgh Playhouse [1] for its part proved educational for a first-time PIL-goer like myself. There seemed to be a substantial lack of gob in the air, which was helpful, I'd forgotten my raincoat. And I didn't spot any bottles or billiard balls either. What I did notice was PIL, the power and the occasional epic grandeur at their live performance. Lydon's magnetic, a compelling sight in his waistcoat, blouse and baggy trousers, and one of the few frontmen in the business who don't even have to try to communicate with an audience. When he does, he keeps it brief: a simple "Hello" as the drama of the intro subsides and the band heads off into 'F.F.F.', a cocky "Well, well, well, thanks for you lot remembering that old one," as 'Pretty Vacant' draws a seizable round of applause. Actually 'Pretty Vacant' seemed quite unnecessary, if quaint, in the context of this set, but at least we can rest assured that we won't be in any danger of hearing 'Anarchy In The U.K.'

"'Pretty Vacant' is there because it's a good tune," said drummer Bruce Smith, as the band congregated around the lobby early, too early, the next day. "We won't play 'Anarchy' because it's different, it's like a standard and we don't want to encourage that nostalgia thing. We're trying to do something new. The important thing about PIL is that John commands a lot of public attention for himself and for the group. He's defined a situation where he can do just about whatever he wants, and he's done that through his own efforts. He's not toed the line with fashion, fads, things like that. He's consistently put out the sort of records that he wants to hear. And I don't think what we're playing now is what people expect to hear, it's a lot more potent and together, and the whole musical standard is perhaps a lot higher."

Bruce and bass player Allan Dias have played together on and off for several years with artists like James Blood Ulmer, and the band that already exists between them helps to strengthen the rhythmic dynamic that is so vital to PIL.

"It's the ideal situation for a bass player and a drummer, working in an environment like John's," remarked Allan. "If you're tuned into the creative force, as it were, it's quite a natural thing. It's about having all your antennae up and receiving signals. That's why we're here."

By now Lydon had arrived in the lobby, wearing a loud checked suit that definitely was not good eye medicine for an unhappy hangover.

It had been a long night that had stretched through to something like 5 a.m., long after Lydon had brought about the inevitable disruption of any further interviewing by inviting the uproarious Lu to the table, long after the decision to drink, drink and be merry had turned into a desperately serious undertaking. The 'Maker' team had been admirable represented by the indestructible Sheehan, while the other half was unfortunately sacrificed as the first casualty of the early hours. And suddenly it had been daylight in a Scottish hotel room, with a sore head and a miserable feeling of "Oh no!"

"And the answer is 'Oh yes!'," smirked Lydon with discernible triumph as he sauntered across the lobby in his coloured checks. If ever the hapless journalist had to pay the price for overindulgence it was going to be at this moment. But the moment passed. And the tiger didn't pounce. Instead he leaned back into a chair, swallowed a headache pill, demanded a stretcher and ordered an orange juice for his dehydration. Fifteen minutes later the entourage got up to go.

"Peace and love!" cracked Lydon as he gathered up his bags and pointed himself at the exit. Well, peace and love to you too, John. I would never have expected it.

A final observation. John Lydon: "I think you'll find the rest of the world pays very serious attention to what's been going on here. America watches England. They love to show the riots on TV there. The Yanks are appalled, and the way it's put over on the TV is as race riots, and they're not. I speak here about the Brixton fiasco, or Toxteth. I don't know so much about the Toxteth one, but I know that Brixton is perfect, half Irish and half black, a perfect combination. We all drink Irish Mist and we all have black and white babies."

NOTES:

[1] Edinburgh Playhouse was the 4th date of the tour on 11 May 1986.

[2] Stoke Victoria Hall was the 1st date of the tour on 7 May 1986.

[3] Sheffield City Hall was the 2nd date of the tour on 8 May 1986.

[4] Julien Temple's movie 'Absolute Beginners', premiered in the UK on 4 April 1986. Temple was a student in Cambridge, not Oxford.

[5] Siouxsie and the Banshees finished their extensive 1981 tour with three gigs in New York (12-14 November 1981), taking three months off after that. It was most probably then that Lydon and McGeoch met.

![]()

© Tom Sheehan